|

| Osmorhiza occidentalis |

|

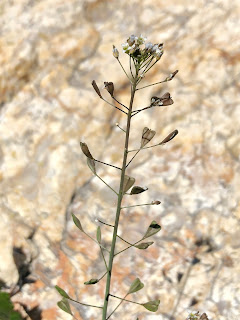

| close-up of the seeds |

But this blog is about eating things, so how does it taste? I think "mountain candy" is how I would describe it. I enjoy the seeds or flower clusters as a trail nibble. They are sweet and have a very powerful flavor (the seeds of most members of the carrot family have a lot of volatile oils in them), so they are best eaten sparingly, like candy. The leaves can develop some bitterness when older, but the young ones have a similar pleasant flavor, but not as strong without all the seed oils. I boiled the leaves for 5 minutes, and they had a milder flavor.

The tea from cooking the leaves had both a pleasant refreshing flavor, and a certain brothiness when hot, and when chilled, it made a wonderfully refreshing drink, without needing any sweetening. The dried leaves can be used to make that same refreshing drink, and adds a great flavor to soups and sauces. I have been adding some of the crushed leaves to flavor my stir-fry sauces, soups, and gravies with delicious results.

The dried root makes an earthy tea with medicinal properties which are useful for respiration and digestion. The flavor reminds me of Osha (Ligusticum porteri), but is not quite the same.

Identifying this plant can be a little tricky, like most members of the carrot family. First, it has the typical compound umbels of the carrot family, with yellow flowers. The leaves are compound, with definite leaflets (not finely dissected into small indefinite segments). Of particular importance are the seeds, which are a little over 1 cm long, thin with shallow lobes running the length of them, smooth (other members of the genus have hairy seeds), and they usually stick straight up from the stem. If all of that matches, break open a seed and smell it. The very strong and pleasant anise scent is like nothing else in my area. Scent seems to be a very good way of identifying members of the carrot family, but you have to learn the scents yourself, because the scientific floras do not try to describe scents.

Finally, a few notes about other species of Osmorhiza. Osmorhiza depauperata, commonly known as Sweet Cicely, is much more common than O. occidentalis in my region. It is easily distinguished by the few rays in its umbels. It only has 3-6 rays in both the umbels and umbellets, which is very unusual in this family, but not in this genus. The seeds are darker, have little hairs, and tend to split in half and hang from their tips when mature. It has very little scent to it, and the leaves can be eaten. Sam Thayer lists several other species which are common in the eastern United States, which are more similar to O. depauperata than to O. occidentalis.